The Man Who Invented the Truth.

Lies used to be scandalous. Now they’re strategy.

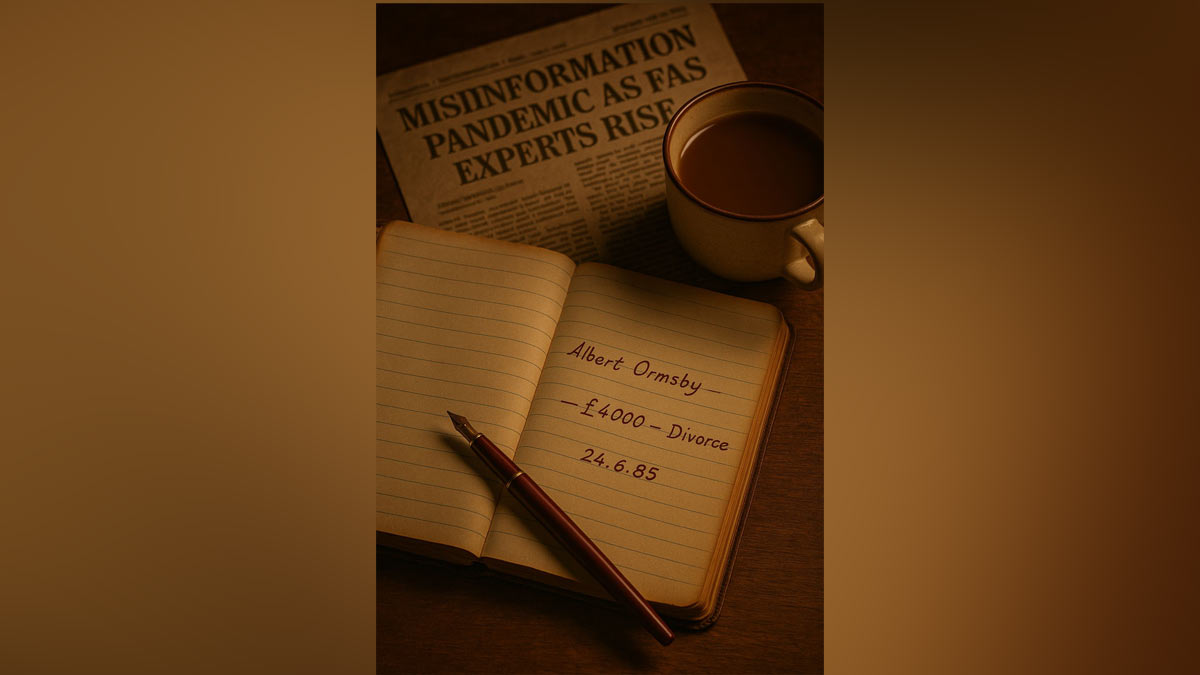

There’s a line in my old legal ledger from 24 June 1985:

Albert Ormsby — £4000 — Divorce.

Written in burgundy ink. No VAT. No cloud storage. Just the human act of noting something that happened.

That act—writing it down, bearing witness—used to be sacred.

We understood that memory was a slippery eel, but paper was loyal.

We believed that the record mattered.

Today?

We’re living in the age of the manufactured truth.

And we seem weirdly… fine with it.

Take the curious case of Peter Navarro—Trump’s economic advisor and China hawk.

To support his tariff arguments, he repeatedly quoted a trade expert named “Ron Vara,” who conveniently agreed with him on everything.

Problem?

Ron Vara doesn’t exist.

He’s an anagram of Navarro. A character Peter invented and then cited—as if he were real—in books, interviews, and policy discussions.

In another age, this would’ve been the stuff of satire or scandal.

Today, it’s barely a ripple.

A shrug, a meme, a joke on late-night television.

We’ve entered an era where quoting fictitious people is just another tool in the spin doctor’s arsenal.

Where falsehoods are no longer buried—they’re brandished.

It’s not just Navarro.

The U.S. government recently published materials quoting sources that don’t seem to exist.

AI-generated content is seeping into news feeds with no verification.

And a worrying number of public figures now use misinformation as a strategy, not a slip.

It’s exhausting.

It’s dangerous.

And worst of all—it’s boring.

Boring because when everything is suspect, curiosity fades.

If all truths are negotiable, why bother asking questions?

If every statistic is spun, every video doctored, every quote invented—what’s the point?

I was trained in a different world.

In a Lancashire law firm that still ran on ledgers and handshakes.

My mentor Geoffrey Knowles—who returned from the Japanese Death Railway to resume legal practice—taught me one rule above all:

“The mind forgets. But the record—if kept properly—won’t lie to you.”

And yet, in 2025, the record itself is under siege.

We now live in what I call the “Post-Veracity Era.”

A place where:

• People make up facts,

• Algorithms amplify them,

• Institutions do little to stop them,

• And the public—tired, distracted, divided—lets it pass.

We used to ask: “Is this true?”

Now we ask: “Does this align with what I want to believe?”

So what’s the antidote?

Attention.

That underrated, unsexy act of looking closely. Of verifying. Of keeping a notebook.

Of writing down something you saw, something that happened, something that mattered.

Because if we lose the art of paying attention, we lose the ability to distinguish between the real and the rehearsed.

Albert Ormsby’s divorce wasn’t earth-shattering.

But it happened.

And forty years later, when his children needed help navigating his estate, I could point to that small burgundy note and say:

Yes. He was here. And this mattered.

In a world of ghost experts and invented truths, I take comfort in that.

That somewhere in my drawer, the real still exists.

So here’s my advice.

Whether you’re a lawyer or a lorry driver, a nurse or a novelist—

Keep a record. Write it down. Be boring if you must.

Because in the end, memory is a trickster. But your notes might just save someone’s legacy.

L’arte di prestare attenzione.

The art of paying attention.

Don’t let it die.

Postscript.

They say history is written by the victors. But sometimes, it’s quietly scribbled by a solicitor with a good pen and a long memory.

This wasn’t just about Albert Ormsby or Peter Navarro—it’s about all of us, and whether we still believe in knowing what actually happened.

Because one day, your notebook may outlast your hard drive.

And your scribble may be the last true thing standing.

Over to You

What’s the smallest truth you’ve ever had to defend?

A detail no one else noticed—but you did.

A memory others forgot—but you held onto.

Leave a comment, a story, or a scrap of truth in the thread below.

Let’s build a little ledger together. One honest entry at a time.